A Different Timeline: Women’s Pre-Code Hollywood – A research essay

by Aubrey Zevallos

“Big Women of the Screen: Concerning Talents That Are Not Expressed With Long Eyelashes” from the Jan. 1922 issue of Screenland. Image from Shelley Stamp.

Due to the disproportionate number of male actors, writers, and directors in the Hollywood film industry as compared to female, we often think of the business as a man’s world. This goes back to film’s beginnings in the early 1900’s: a time which modern perspective views as comparatively antiquated in terms of social progressivism, feminism, and equal rights. While this isn’t an incorrect perception, the truth is that early Hollywood was surprisingly progressive compared to other fronts of American life when it came to race and gender.

In fact, there were several African American film studios that produced, directed, and wrote films with entirely African American casts in early Hollywood; studios that were lost in time as the film industry “Code” came to the forefront. A number of popular actors and actresses were of mixed or non-white racial ancestry. This diversity would not be seen again for decades, with even the modern film industry continuing to lack major representation of non-white ethnicities.

The same goes for women: Women had a huge role in all facets of early Hollywood. They acted, wrote, directed, filmed, edited, and produced films, and created, owned, and ran film studios. Women in pre-Code Hollywood had more diverse roles, more creative power, and more creative independence than they did in the decades after the Code. Arguably, women continue to have less power in today’s film industry than they did during the birth of film.

Prolific filmmaker Frances Marion sitting in a Director’s Chair

The Code changed the course of Hollywood for women and the roles they were allowed access to, both on-screen and off.

But the Code didn’t do this on its own simply by existing. Studios like Universal made conscious decisions to change their pre-Code process in a way that edged women into much smaller roles in the industry. The studio system, active from 1927 to 1948, also played a role in reducing women’s independence in the industry. Additionally, the Great Depression was a major player in the changing landscape of film in the 1930’s.

The studio system certainly would have functioned differently without the Code. However, it’s difficult to say what the effects of the Depression on film would have been without the “soft” Code of the 1920’s, followed by the strictly enforced Code of 1934 which would last, with immeasurable reach but in ever-diminishing form, until 1968.

Ida Lupino, one of the few female directors working in Code-enforced Hollywood. Image Source

When we talk about “Pre-Code Hollywood”, we must establish what time period we mean:

In 1924, former Postmaster General William Hays was hired to temper Hollywood’s image with a list of allegedly “moral” recommendations for filmmakers. These guidelines were dubbed “The Formula”. Note that Hays had no experience or interest in the film industry or the art of film except as to follow orders to refine its alleged immorality.

In the early 1900’s filmmakers weren’t much concerned with following a formula — they were exploring, inventing, and creating with new and exciting technology. In 1927, the oft-ignored Formula was refined into a list of “Don’ts and Be Carefuls”. These were the foundation of the Code as we know it, although this list preceded the period most scholars call “Pre Code” due to its lack of enforcement.

1927 MPPDA memo excerpt outlining some of the “Don’ts and Be Carefuls.” Courtesy MPPDA Digital Archive. Note that “sex perversion” is understood to refer to both sex in general and homosexual relations in particular; also note that “white slavery”, but not “black, indigenous, Hispanic, Latino or Asian slavery”, was forbidden.

The Formula was like an annoying little sibling that occasionally “told on” filmmakers to the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, getting them a slap on the wrist — but they still made the films they wanted to. The “Don’ts…” list was that same sibling, a little older and a little louder. Sometimes filmmakers had to alter their content to please this list, but most of the time, they still negotiated their way into fulfilling their creative visions as desired.

Despite the lack of enforcement, it’s important not to ignore the effects of Hays’ preceding lists on the strictly enforced Production Code Administration system that would follow — thanks to devout Roman-Catholic Joseph Breen — nor the effects both codes had on the industry overall. The rigid and oppressive Code that followed was created and enforced by Breen, despite being erroneously referred to as “the Hays Code”.

“Pre Code” is often used to refer to the advent of talkies (film with audible dialogue) up until Breen’s code, skipping over decades of silent film. For this essay, I will use “pre Code” to mean from the very beginning of the film industry, with special focus on the silent film era, up until Breen’s restrictions that altered the course of Hollywood film production in 1934.

1934 Motion Picture Production Code cover

Contrary to modern perception on gender restrictions of the times, women worked actively in all aspects of the film industry in the early 1900’s. Between 1911 and 1920, twenty-percent of silent films were written solely by women, and twenty-five percent had female writer co-credits (Slide, 2012). One of the major female filmmakers in the early 1900’s was a French woman named Alice Guy (married name: Alice Guy-Blaché).

Filmmaker Alice Guy-Blaché poised at the camera. Image Source

Guy directed over 180 short films in France from 1896-1906 before immigrating to the U.S., where she established an independent studio, Solax Studios, and became the first female executive officer of a film studio. Her studio produced the first film with an all-black cast, A Fool and His Money, in 1912. Guy was the first woman to own a film studio and one of the first film directors of any gender to shoot on location.

Another extremely successful trailblazer was Frances Marion: Marion was a screenwriter, journalist, author, and film director who wrote over 300 screenplays. Marion was the first writer of any gender to win more than one Academy Award for writing.

Frances Marion, Photoplay magazine, 1918

Marion worked with Lois Weber, another early Hollywood dynamo: Weber was an actress, screenwriter, producer, and director who was the first American female director to start and run her own movie studio (Lois Weber Productions, 1917).

Lois Weber on set, 1927; Photo from the Bison Archives

Examples like Guy, Marion, and Weber abound.

Zora Neale Hurston was better known as a novelist, but is thought to be the first black female filmmaker. Hurston was a playwright, director, and screenwriter who made at least three films in the 1920’s. She won an award for her play Color Struck in 1925 and went on to work for Paramount Studios.

Zora Neale Hurston. © Barbara Hurston Lewis, Faye Hurston, and Lois Gaston; Image Source

Eslanda Goode Robeson was another pioneer: Robeson was an actress, talent manager, and writer who had a PhD in anthropology and helped found the Council on African Affairs. In addition to her roles in the film industry, she was the first black person to be hired in the surgical pathology department at New York City’s Presbyterian Hospital; while she also managed her husband Paul Robeson’s film and theater career. She starred in 1929’s Borderline, a film depicting at least two off-limits topics during the Code: a multi racial relationship, and a bisexual character. Frustratingly, Robeson offered some advice to the Scottish director of the film to help him more realistically portray black people. He rebuffed her advice and eventually refused to let her even see the film.

Eslanda Goode Robeson. Image Source

Actress and screenwriter Gene Gauntier wrote 42 screenplays and directed the feature The Grandmother in 1909; she started the Gene Gauntier Feature Players Company with her husband and friends, wrote scenarios, and performed her own stunts.

Gene Gauntier, film still from ‘On the Firing Line’, taken spring 1913; The Moving Picture World, May 31st, 1913, Vol. 16, No. 9, p. 926

Silent film actress Marion Leonard was the first “star” actress to start a film company, with her husband Stanner E.V. Taylor.

Mexican-American actress Beatriz Michelena was one of the first Latina actresses to find success in Hollywood. She founded Beatriz Michelena Features, a film studio that was active from 1917 until 1920.

Beatriz Michelena (a/p/o) in Unwritten Law (1916), California Motion Picture Corporation. RB. Image Source

Actress, director, producer Florence Lawrence started Victor Film Company with her husband Harry Solter. Significantly, Victor Studios was absorbed into Universal Studios in 1917; prior to the Code, Universal employed many women in creative roles.

Florence Lawrence, whose acting career was sunk after she suffered severe burns from saving a crew member in a fire.

The examples of women in diverse professional roles, “doing it all”, so to speak, were everywhere in silent film.

In 1914, writer, producer, director, and actress Helen Holmes starred in a groundbreaking series called The Hazards of Helen, in which the actress portrayed an independent, brave, and clever heroine who did all of her own action stunts in the twenty-six episode adventure series. Holmes later went on to start her own studio, Signal Film Productions, with her husband J. P. McGowan.

Helen Holmes, 1915

Actress and comedian Flora Finch started the Flora Finch Company (1916) and the Film Frolics Picture Corporation (1920). Finch had a starring role in more than 300 silent films in the early 1900’s.

Clara Bow and Flora Finch in The Adventurous Sex, 1925

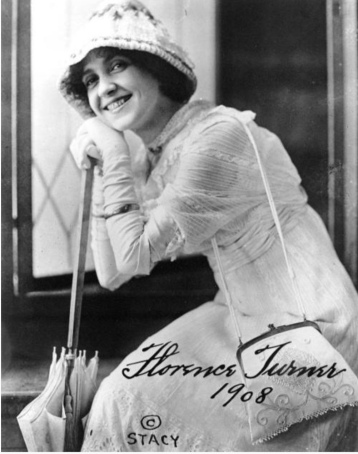

Florence Turner was known as the “Vitagraph Girl” in the early 1900’s for her appearance in Vitagraph shorts; Turner also wrote screenplays and founded Turner Films, Inc, in 1913, creating more than thirty short films.

Cleo Madison, working for Universal Films, wrote and directed ten shorts and two feature films, alongside her acting career from 1913 to 1924.

Publicity shot of Florence Turner from the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences / Academy Film Archive

The working women of early Hollywood were aware of the unique landscape they inhabited in the film industry. Actress and producer Gloria Swanson described the freedom of female film creatives like Clara Kimball Young, a popular actress who was the second star actress to start her own production company (Clara Kimball Young Productions):

“In what other business,” asked Swanson, reminiscing on meeting Young, “Could this delightful elegant creature be completely independent … turning out her own pictures … dealing with men as her equals, being able to use her brains as well as her beauty, having total say as to what stories she played in, who designed her clothes, and who her director and leading man would be.” (Hallett, 2017)

We can’t talk about powerful women in early Hollywood without talking about Mary Pickford. Pickford is one of the most famous female entrepreneurs of early Hollywood, and with good reason. But with the preceding examples we can see that Pickford was not the only female jack-of-all-trades working independently and creatively in the burgeoning film industry.

In 1916, prolific actress-producer and shrewd businesswoman Mary Pickford started her own motion picture production company, the Mary Pickford Corporation.

Prolific Hollywood businesswoman Mary Pickford on set with fellow dynamo Frances Marion

Mary Pickford behind the camera. Image Source

Three years after founding the Mary Pickford Corporation, the venture gave way to the founding of the motion-picture studio United Artists, a studio which is still active (albeit in a much different form) today. Pickford — along with Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and D. W. Griffith — founded U.A. in an effort to regain some independence and creative control from what was quickly becoming a “studio system”. The conglomeration and vertical integration of the studio model into a contracts system shifted power from independents to groups, a power shift that would gradually become more and more exclusive.

In a 1924 interview with Photoplay, Gene Gauntier waxed reminiscent about her days in the film industry (1906-1920):

“In addition to playing the principal parts, I also wrote, with the exception of a bare half-dozen, every one of the five hundred or so pictures in which I appeared. I picked locations, supervised sets, passed on tests, co-directed with Sidney Olcott, cut and edited and wrote captions (when in the United States), got up a large part of the advertising matter, and, with it all, averaged a reel a week. It was work in those days—but creative work, blazing the trail.” (Photoplay, 1924)

Blazing the trail, indeed. Sadly, a combination of wartime, a studio system, the Great Depression, and of course, the Code, would shrink and alter the course of that trail in the decades that followed.

Among all of these women, prolific director, editor, film cutter, and screenwriter Dorothy Arzner was one of the few women to maintain a strong creative career both before and during the Code.

Dorothy Arzner, overseeing the camera work while holding what may be a megaphone or frame viewing tool. Source

Dorothy Arzner and Clara Bow during the making of The Wild Party (1929). Source

Arzner’s film career lasted from 1919 to 1943. Director Frances Marion’s film career lasted until the 1970’s. Lois Weber made between 200 and 400 films, but her career, like that of many women in film, ended in the 1930’s.

After Weber’s career at Universal ended, Universal did not have another female director working with them until the 1980’s (Cooper, 2014). Most other female creatives’ film careers ended promptly by the 1930’s: During the rise of the Code.

Despite the existence of the Hays list of “Don’ts and Be Carefuls” (1927), the MPPDA (1922), and the Motion Picture Production Code (1930), studios continued to resist censorship and forced edits into the early 1930’s. When this came to women and heterosexual relationships, this meant that sex was portrayed in abundance during pre-Code: in pre-Code films, women were allowed to have sex, even if not married. Women were allowed to show their bodies and use them as they saw fit. Women were allowed to have power in relationships, and could make sexual innuendo and jokes. Actress, singer, playwright, screenwriter, and comedian Mae West was the queen of innuendo, but there were many others.

What’s more, it was not infrequent that women were writing or filming these raunchy jokes and sensual stories themselves. Pre-Code films “featured plots where a woman would choose a lover over a husband, or sell herself to get what she wants, or shoot someone who was in her way — and not be punished by the final frame” (Kurtz, 2002). One of the Code’s stipulations for allowing the slightest “moral shortcoming” — as determined by Breen — to be included in a film, was that the “offending” character must suffer by the final scene. This often meant death or jail.

Barbara Stanwyck in one of the most well-known pre-Code films, which was released shortly before the Code would have made its production impossible: Baby Face (1933). Image Source

Additionally, pre-Code film featured at least two same-sex kisses. Such physical affection between same sex actors would not be seen again until the 1970’s, after the Code was dissipated. In 1927’s Wings, two male characters share a passionate, prone embrace with a goodbye kiss. The film was also embraced, winning Best Picture that year at the Oscars (the Academy, by the way, was founded by Mary Pickford and co).

Wings, 1927; Winner of Best Picture at the first Academy Awards ceremony in 1929. Image Source

Marlene Dietrich, whose exciting pre-Code career continued in a more subtle yet very successful path during the Code, had the first female-to-female onscreen kiss. In 1930’s Morocco, Dietrich broke two cultural norms when her character dressed in a tuxedo and casually kissed a female audience member.

Marlene Dietrich in Morocco, 1930. Image Source

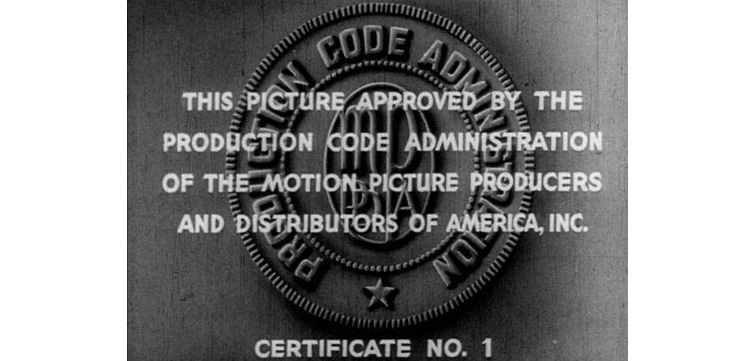

Then, came Joseph Breen and the Production Code Administration. Ignoring the Code was no longer a choice: the PCA required its stamp of “moral” approval on every film in order for it to be exhibited at all, punishable by a fine of $25,000.

Screenshot of the PCA “seal of approval”. Image Source

Joseph Breen was the head of the PCA from its inception in 1934 until 1954. For twenty years, American cinema was bent to the moral wills and rigid whims of a middle-aged, Roman-Catholic, anti-Semitic, former government service worker with no experience in the film industry or in any creative endeavor. His anti-Semitism is particularly worth noting because many of the people involved in the production and exhibition of films at the time were of Jewish heritage.

We have no way of knowing exactly how much Breen’s religious beliefs and anti-Semitism influenced his choices in censoring a creative and non-Christian Hollywood. But we do have the Code itself, with line after line of prohibited material, and we have in the history of “Coded” film examples of what didn’t make the cut — or was later cut and re-shot.

The Code resulted in many filmmakers having to alter endings, either adding unwanted scenes during filming, or even having to re-shoot and add entire scenes to meet the Code’s demands. But it wasn’t just gangsters and criminals that caused the Code’s administrators to call for cuts and re-shoots; “loose women”, sex workers (which were in abundance in pre-Code films), and infidelity had to be punished just as harshly as burglary and murder. The Code took its censorship of sexual relations even further. Sexual activities outside of marriage must not appear “beautiful or attractive”, and must be punished.

While some parts of the Code were written clearly and specifically, others were more vague and arbitrary — for example, warning against any film that would result in “lowering the moral standards of those who see it” and “moral evil” — thus allowing most of the judgment of acceptability to fall squarely with Breen. It’s no wonder he claimed “work exhaustion” when he finally retired — censoring that much art is a lot of work.

A promotional photo of actress Joan Blondell in 1932, banned a few years later under the Motion Picture Production Code. Image Source

The Code changed everything. As LaSalle writes in Complicated Women: Sex and Power in Pre-Code Hollywood (2000), the restrictions of the Code “ensured a miserable fate — or at least a rueful, chastened one — for any woman who stepped out of line.” LaSalle mourns the Pre-Code era, asserting that during the Code “whole genres and careers were destroyed, while well-written scripts were heavily cut or disallowed outright. The Code wasn’t simply about getting rid of naughty words or translucent costumes. Breen saw immorality hiding behind the most innocent tales; some ideas, he felt, simply couldn’t be expressed in any form.”

All of this restriction meant women were leaving film, by choice or by force, both behind the scenes — where they couldn’t make the films or use the creativity that they wanted to — and in the scenes. Actresses were being forced to take, or later be edited into, smaller and less interesting, less significant, and less diverse roles in film.

As the Code rolled out, the studio system was infringing on the creativity and license of women as well. As Mark Garrett Cooper writes in Universal Women: Filmmaking and Institutional Change in Early Hollywood (2014), Universal Studios “made women directors disposable by insisting that their films be womanly”. We can only imagine what the male heads of Universal meant by ‘womanly’ in that century, but it did not fall in line with the new woman of the 1920’s and 30’s.

This meant that Universal went from being a studio employing an unusually high percentage of women (though still far lower than the male percentage), to almost zero women. After their glorious early days of female creatives in the early 1900’s, from 1920 to 1982, Universal had only employed a single female director (Lois Weber).

According to LaSalle, the Code was designed “to put women back in their place. The good ‘bad’ woman who had been delighting audiences simply disappeared. Women were no longer to be as independent or free”. Paraphrased by Kurtz, one of LaSalle’s example is the case of the film Mary Stevens, M.D. from 1933: the film ends with the female protagonist Kay Francis “affirming her place as both a woman and a professional”, a pre-Code ideal.

A few years later, during the restrictions of the Code, The Flame Within (1935) ends with the female protagonist Ann Harding “renouncing her career as a psychiatrist to marry a man who doesn’t approve of her working”. Very Code. In Kurtz’s words, “the women who did survive had to play galling scenes at the end of countless films where they’d knuckle under to male domination” in order to fulfill the requirements of the Code.

Still from Mary Stevens, M.D. Image Source

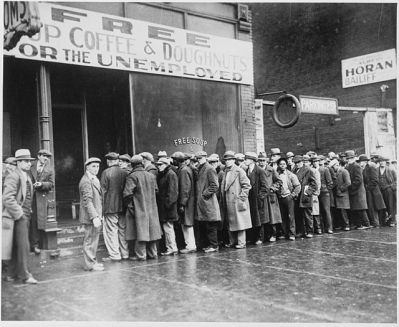

Meanwhile, the Great Depression saw some studios struggling to stay afloat, with Paramount Studios nearly going bankrupt, and many others disappearing forever.

This financial panic and strife meant people were not willing to take as many risks, or fluff as many budgets; particularly with the Code’s $25,000 fine hanging over their heads if they even thought about being daring.

Karen Wahard Mahar’s 2006 book Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood examined the shifting atmosphere of the film industry: from the “all hands on deck” attitude that was distinctly ungendered, asking the same work of everyone involved; then giving way to distinctly segregated roles. Mahar also decries the interest of investors from Wall Street that caused the film industry to take a sharp veer towards pure entertainment, abandoning the daring complexities of role-questioning and experimentation that defined early Hollywood.

A line of unemployed workers during the Great Depression. Image Source

It was the unintentional collusion of the World Wars of 1914-1918 and 1939-1945, the Depression of 1929-1941, the studio system of 1927 to 1948, the Hays Code of 1922-1934, and most directly, the PCA Code of 1934-1968, that led to a creatively weakened and progressively stagnant film industry as compared to the early 1900’s.

Studios, financial strife, and the Code grabbed a young and vibrant Hollywood by the neck and squeezed. What followed was a different beast. Although the Code was dispelled officially in 1968, women have still been relegated to very specific roles up until the most recent decade of film history (the 2010’s). This is, undeniably, a remnant from decades of the Code during Hollywood’s crucial time of development.

Additionally, there are still very few women directors and writers as compared to the pre-Code era and the silent film industry. According to the Center for the Study of Women in Television & Film, female directors make up only 8% of all film directors; they also make up only 11% of screenwriters in the industry.

To be sure, women did not disappear entirely from the film industry, nor did they stop fighting for better roles. Many women and men continued to fight the Code and find little ways around it, or through it. Throughout the Code era, filmmakers pushed the limits more and more, until finally they pushed it out in the late 1960’s.

Image Source. Poster for The Moon is Blue (1953). Filmmakers pushed the Code little by little, and even began to ignore it by the 1950’s, thanks in no small part to Otto Preminger and F. Hugh Robert’s The Moon Is Blue.

I might be so daring as to argue that 1900-1920 should be the real “Golden Age” of Hollywood:

When people of all races and genders had at least a fighting chance in the film industry, and could create their vision, even if it didn’t mean fame or fortune; when women could say “yes” when they wanted to and “no” when they didn’t; when creative visions abounded and the excitement and novelty of film was a heady concoction enjoyed by the many rather than the few. This was young Hollywood. An almost mythical “Hollywoodland“, as the sign read until 1923.

Lois Weber, one of the most prolific female directors in early Hollywood whose career spanned decades, said the following in the heyday of pre Pre-Code:

“In moving pictures I have found my life’s work. I find at once an outlet for my emotions and my ideals. I can preach to my heart’s content, and with the opportunity to write the play, act the leading role, and direct the entire production, if my message fails to reach someone, I can blame only myself.” This was in 1914.

And as Gene Gauntier said of the period, “We were always discovering new possibilities, and each little success or surprise fed our enthusiasm.”

The early years of Hollywood were a bright and promising place for female creatives; an arrested dream that lives on in the few reels that survived the tests of time.

Further Research Sources

Beauchamp, Cari. Without Lying Down: Frances Marion and the Powerful Women of Early Hollywood. New York: Scribner, 1997.

Blaetz, Robin. “Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio & Television, vol. 29, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 258–260.

Cooper, Mark Garrett. Universal Women: Filmmaking and Institutional Change in Early Hollywood. University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Feeley, Kathleen. The Journal of American History, vol. 98, no. 1, 2011, pp. 224–225. JSTOR.

Gaines, Jane M. Pink-Slipped: What Happened to Women in the Silent Film Industries?, University of Illinois Press, Urbana; Chicago; Springfield, 2018, pp. 16–32.

Hallet, A. Hilary. How Women Built Early Hollywood – And Transformed Los Angeles. KCET.org. November 7, 2017.

Koszarski, Richard. An Evening’s Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915–1928 (University of California Press, 1994): 223.

Kurtz, Steve. “Hollywood’s Second Sex.” Reason, vol. 33, no. 10, Mar. 2002, p. 75.

LaSalle, Mick. Complicated Women: Sex and Power in Pre-Code Hollywood. 2000.

Slide, Anthony. Early Women Filmmakers: The Real Numbers. Film History, Vol. 24, No. 1, Film Histories (2012), pp. 114-121

Smith, Frederick James. “Unwept, Unhonored and Unfilmed”. Photoplay. July 1924: 67 & 101 – via Lantern.